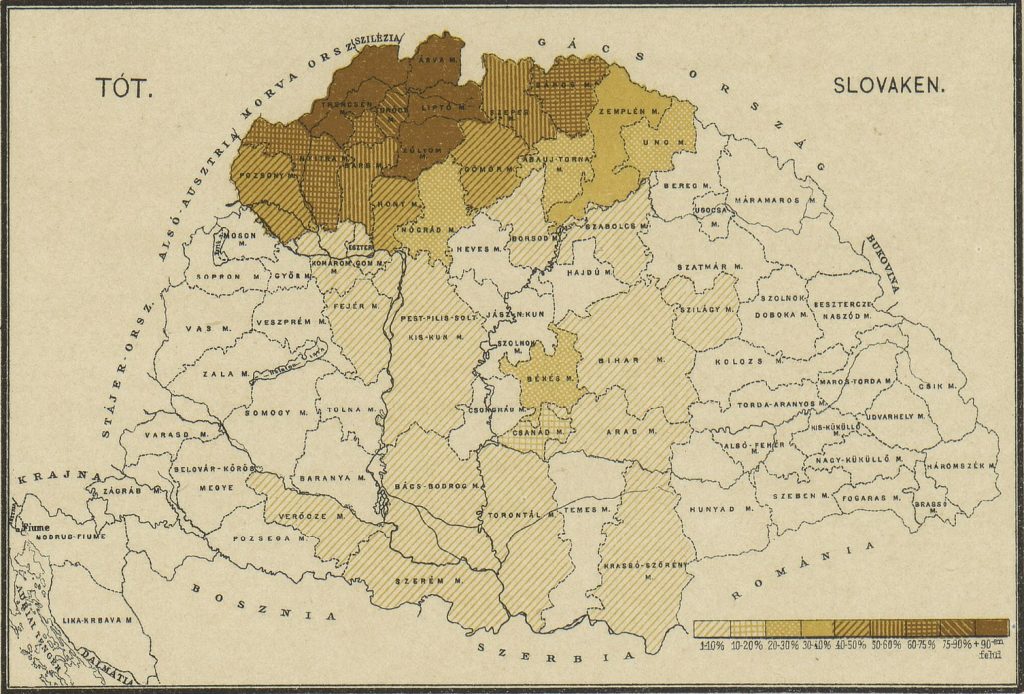

According to the 1880 census, approximately 1.49 million people in the northern areas of the Kingdom of Hungary declared Slovak as their maternal language, a number that increased to 1.68 million by 1910. This Slovak-speaking population formed a continuous and compact settlement stretching along and below the Carpathian mountain range, encompassing eleven counties where native Slovaks constituted either an absolute or relative majority: Pozsony/Prešporská, Nyitra/Nitrianska, Trencsén/Trenčianska, Árva/Oravská, Liptó/Liptovská, Turóc/Turčianska, Zólyom/Zvolenská, Hont/Hontianska, Bars/Tekovská, Szepes/Spišská, and Sáros/Šarišská. However, when accounting for other adjacent counties where Slovaks were a minority, as well as diaspora communities and enclaves in the central and southern regions of the Kingdom, the total number of Slovaks reached approximately 1.95 million in 1910, representing roughly 10.7% of the Kingdom’s total population of 18 214 727.

Within this predominantly Slovak-inhabited region, several German-speaking enclaves were present, totaling approximately 221 000 in 1880, a number that declined to 198 000 four decades later. This decline was primarily attributable to processes of linguistic assimilation, as many German speakers adopted Hungarian as their declared mother tongue in subsequent censuses. These enclaves were particularly concentrated in Pozsony, Zólyom, Szepes, and Turóc counties. The second largest group were the Hungarians, though their presence in the northernmost counties (such as Trencsén, Árva, Liptó, and Turóc) was limited to only a few hundred or a few thousand individuals, primarily members of the administrative apparatus, state employees, and their families. The western and northern boundaries of Slovak settlement coincided with the state borders of the Kingdom of Hungary, bordering the composite provinces of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. To the west, Slovak-inhabited areas bordered the Cisleithanian province of Moravia, while to the north, they bordered Galicia. To the east, Slovak settlement gradually transitioned into Ruthenian-inhabited areas, while to the south, it bordered Hungarian-speaking regions. The linguistic boundary of the Slovak-speaking population was characterized by a gradual transition into other Slavic dialects in the west, north, and east. In contrast, the southern boundary, where Slovak and Hungarian languages and cultures met, was more distinct, resulting in functionally bilingual populations in the contact areas.

The predominant religious denomination among Slovaks was Roman Catholicism, to which approximately 70% of the population adhered. Slightly less than a quarter (approximately 23%) were members of the Lutheran Evangelical Church, while about 5%, primarily concentrated in the eastern counties of Szepes and Sáros, belonged to the Greek Catholic Church. The Lutheran community, often regarded as an ethnic church, was most strongly represented in the centrally located counties of Turóc and Liptó, where it made up approximately 52% and 42% of the population, respectively. These counties also formed the core areas of Slovak nationalist activity throughout the period.

The dominantly Slovak-inhabited counties (including their non-Slovak populations), if considered as a unit, had a slightly lower share of the population engaged in agriculture than the Kingdom’s average, with 65% employed in the sector compared to the all-state figure of 68%. Small and petty landowners—those owning or renting land below 5.8 hectares—who relied on family labor or, at most, one or two hired farm laborers, constituted two-thirds of the peasantry. A large portion of the petty peasantry and landless agricultural workers regularly engaged in seasonal labor in the southern parts of the Kingdom (after the turn of the century, up to 80 000 annually). Apart from this internal labor migration, Slovaks also accounted for the proportionally highest rate of overseas migration from the Kingdom, with emigration rates reaching 26–28% in Sáros and Szepes counties, while in Árva, Turóc, and Liptó counties, rates ranged between 14–19% in the decade after the turn of the century. The rate of return migration during the 1880s and 1890s was relatively high, reaching up to 75%, but it declined to 30% after the turn of the century (with 116 000 returnees out of 395 000 emigrants between 1899 and 1913). Despite the gradual decline in return rates, Hungarian state authorities perceived returnees as potentially more inclined to support the Slovak nationalist movement and to incite unrest among the peasantry against the state and its regime.

The literacy rates of the Slovak population, particularly among the peasantry, were relatively high within the Kingdom, not falling significantly behind those of Hungarians and the most literate German population. In 1900, among individuals aged 15 to 49, the illiteracy rate was 24.3% among Slovaks, compared to 17.3% among Hungarians and 10.8% among Germans. The overall illiteracy rate for the entire Kingdom within this age cohort was 34.4%. This relatively favorable literacy level persisted despite the gradual elimination of Slovak as a language of instruction from elementary education, which was increasingly replaced by Hungarian. In 1876, there were 2016 elementary schools with Slovak or mixed Slovak-Hungarian instruction; by 1913, this number had declined to a mere 354. Additionally, there was not a single educational institution above the elementary level that provided instruction in Slovak or even offered Slovak as a subject. The only three Slovak-language gymnasia, which had existed previously, were abolished by the government in 1874. After the turn of the century, Slovak was used as a language of instruction only in elementary schools maintained by the Roman Catholic and Evangelical churches, particularly the latter.

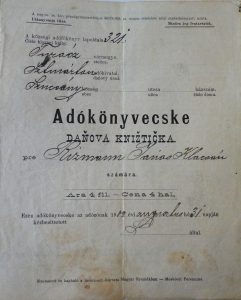

The language question—the demand for the use of Slovak in public administration and education—was one of the primary concerns of the Slovak nationalist movement. From the 1880s onward, the state systematically marginalized Slovak and other non-Hungarian languages in public administration and official communication with citizens. Although in rural areas, informal communication between officials and peasant applicants often continued in Slovak out of necessity, Slovak national activists frequently highlighted cases where the language barrier and the compulsory use of Hungarian—an unintelligible legal and administrative language for many Slovak-speaking peasants—placed them in a disadvantaged position. Heavy taxation was another central issue that resonated with the Slovak peasantry. From the 1890s onward it became a key element of the nationalist mobilization discourse, which increasingly targeted the rural population. Regular state taxes imposed on small-scale farmers amounted to approximately 50% of their agricultural yields, while additional special levies for infrastructure development projects, such as railway construction, could raise the total tax burden to nearly two-thirds of their total produce or earnings.

Although most Slovak nationalists envisioned the Slovak national territory as spanning eleven to thirteen or even fourteen counties stretching from west to east across the northern region of the Kingdom of Hungary, their organizational efforts and political activism were primarily concentrated in just seven counties: Pozsony, Nyitra, Trencsén, Árva, Liptó, Turóc, and Zólyom. Across this broader region of 11 to 14 counties, there were approximately 50 constituencies where Slovak voters—primarily peasants—formed the majority, electing around 50 deputies to a parliament of 413 members. Before 1914, Slovak nationalists focused their organizational network-building efforts and activism mainly within the aforementioned seven counties, which covered much of the western and central part of the Slovak-inhabited territory. During the four parliamentary elections between 1901 and 1910, Slovak nationalists were able to field candidates in 17 constituencies across these counties. The BENASTA focuses primarily on these seven counties while at the same time also taking into account developments in other regions, recognizing their significance in the broader context.