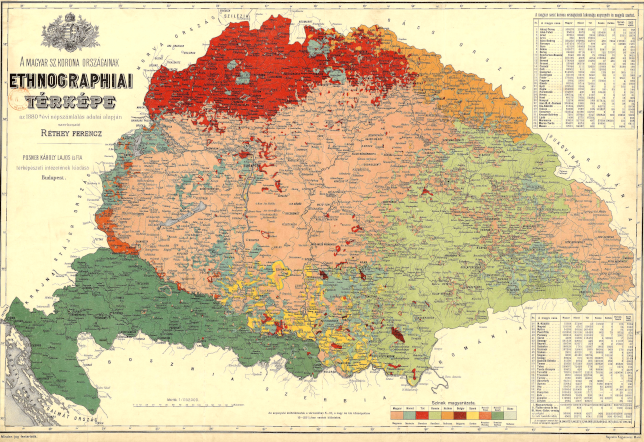

Censuses between 1890 and 1910 found 2.6 to 2.9 million native Romanians in the Kingdom of Hungary. At least the number of people externally identified as Romanians must have fallen in the same range, as Romanian first language was generally equated with membership in one of two ethnic churches, the Romanian Greek Catholic and the Romanian Orthodox. Both of these churches used Romanian for their liturgy.

The lands Romanians inhabited West of the Carpathians were not limited to historical Transylvania, a separate province under Habsburg rule until 1848 or 1867. They also made up the bulk of the population in the eastern stretches of Hungary proper to the west and parts of the Military Frontier in the Southern Banat, which stood under Habsburg military rule until the 1870s. These lands had a diverse history before the Austro-Hungarian Settlement of 1867 and were annexed to the Kingdom of Romania after the First World War.

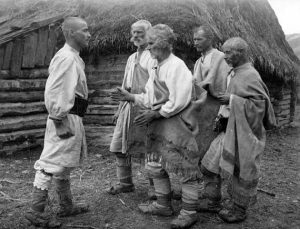

The overwhelming majority (86% in 1910) were peasants who made their living from agricultural labour. The vast majority had also been serfs or landless cotters (jeleri) under seignorial rule until 1848, with the exception of Romanian petty nobles (concentrated in a few areas) and the border guards of the Military Frontier. Prior to 1851, the Military Frontier also extended over the border strip of Transylvania, including two Romanian regiments. Since most former feudal landlords did not belong to the Eastern rite and tended to speak Hungarian, the class distinction between them and former serfs easily acquired an ethnic colouring. The fragmented map of noble estates in Transylvania contrasted with the more latifundia-heavy Banat and Eastern Hungary, while the farm size among the emerging independent Romanian peasantry was relatively even. In some regions, the state played a prominent role as a landowner.

There were many contact areas where Romanians and Magyars shared much of the same local peasant culture, but intermarriage was rare. Ethno-confessional boundaries were more rigid in the formerly privileged Saxon Land of Transylvania, and wealthy Saxon peasants often employed local Romanians as farmhands and day labourers. However, most Romanians lived their lives in environments where ethnic others, in so far as they were present, were not peasants.

Romanian confessional schools increased literacy rates to over 50% in certain areas, although parts of the Romanian-speaking countryside, especially in the highlands, remained illiterate. In addition to schools, other Romanian institutions such as saving banks, choirs and amateur drama groups also relied on confessional and local power networks. Moreover, parish priests and schoolteachers often channelled nationalist messages and formed a bridge to the national movement.

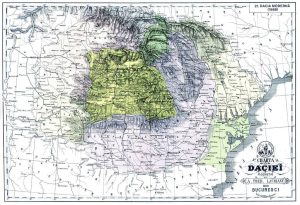

Although Romania emerged as a kin state across the borders almost in lockstep with Austria-Hungary and the concept of national unity took on a strong symbolic role, the Romanian national movement was not necessarily irredentist. In fact, the Romanian minority press regularly appealed to Romanians’ traditional loyalty to the Habsburg dynasty against the supposedly rebellious and treacherous Hungarian/Magyar establishment. Romanian national activists opposed the constitutional setup installed in 1867 and boycotted elections in most constituencies until the 1900s. The keystone of Romanian nationalism was the autochthony argument resting on the idea of modern Romanians’ descent from the veterans of Emperor Trajan in the Roman province of Dacia, played out against the dominant Hungarian discourses of historical rights and status quo.

The so-called Austro-Hungarian Settlement of 1867 gave Hungary exceedingly far-reaching autonomy, which later included a separate Hungarian citizenship and only stopped at foreign affairs. In these new frames, Hungarian governments inaugurated state nation-building and homogenizing language policies, which also hit people in the villages. Even though county and local autonomies placed some limits on central government power, most county elites also supported Hungarian nation building. In this context, the Romanian minority was in particular singled out as a threat to the security of the Hungarian state. In addition to the resulting “excess grievance” (the sociologist Oszkár Jászi’s term), Romanian peasants shared with their non-Romanian peers the burdens of a catching-up, modernizing state, with its ubiquitous gendarmerie, mushrooming regulations and spiralling bureaucracy, and the accompanying rise in direct and indirect taxes, including a high and regressive land tax.

With the exception of a soi-disant Marxist period in the 1950s and 1960s, Romanian peasant politics and peasant‒state relations in Dualist Hungary have been rarely studied outside a militant nationalist historiographical framework. This historiographical tradition has traditionally focussed on the Memorandum Trial of 1894 as the high point of popular nationalist mobilization. However, while claims about the people’s “national struggle” against Hungarian rule serve some political legitimizing function, these historians have interpreted the peasants as a subservient appendage of the national movement.