Population censuses from the turn of the century reveal that approximately every fourth inhabitant of the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia was an Orthodox Christian who declared Serb or Croat as their mother language. Between 1880 and 1910, their numbers rose from 497,746 people or 26,30% of the Croatian-Slavonian population to 644,955 people or 24,6% of the Kingdom’s inhabitants. The great majority of Orthodox believers were also self-declared native speakers of Serb or Croat (98,8% in 1910), and the members of this community formed the demographic “target audience” for Serb nationalist activism in late-Habsburg Croatia-Slavonia.

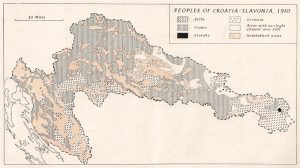

Ethnographic map of Croatia-Slavonia according to the 1910 census. Produced by Royal Navy Intelligence, 1944, with an emphasis on Croat and Serb majority territories. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Ethnographic map of Croatia-Slavonia according to the 1910 census. Produced by Royal Navy Intelligence, 1944, with an emphasis on Croat and Serb majority territories. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

As may be discerned from the above map, the Orthodox South Slav population was unevenly distributed across Croatian-Slavonian territory. Like in the neighboring Kingdom of Hungary, the Croatian-Slavonian administration system rested upon the institution of the county (županija). In absolute terms, the largest number of Orthodox South Slavs lived in the eastern-most County of Syrmia – 183,109, or 44,2% of the county population in 1910. However, their relative share was highest in the Lika-Krbava County, where they totaled 107,172 people or 51,2% of the county population.

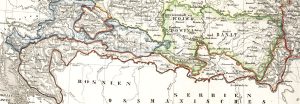

The Croatian-Slavonian and Banat Military Frontier, ca. mid-19th century. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The Croatian-Slavonian and Banat Military Frontier, ca. mid-19th century. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The concentration of the Orthodox population alongside the Kingdom’s southern and eastern borders was not coincidental and roughly coincided with the historic borders of the Habsburg Military Frontier. Established in the 16th century as a bulwark against the expanding Ottoman Empire, it was a separate legal territory directly administered by the Austrian military authorities until the early 1870s. The military authorities granted religious freedom to the local Orthodox population, which had been migrating to Croatia from Ottoman-ruled Bosnia and Serbia since the 15th century, while also freeing local peasants from feudal obligations in exchange for military service. From this institution arose a specific society of free peasant-soldiers who lived under a different legal order than their bonded countrymen in so-called civil or provincial Croatia. The legal dualism between the Krajina and the Provincijal was finally abolished in 1883 with the former Frontier’s integration into Croatia-Slavonia’s civilian administration.

The Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia and its counties in green, cca. 1890. Source: Digitalne zbirke NSK u Zagrebu.

The Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia and its counties in green, cca. 1890. Source: Digitalne zbirke NSK u Zagrebu.

With 91,43% of the community employed in agriculture according to the 1900 census, the Orthodox were the most rural among all confessional groups living in Croatia-Slavonia. Peasant society had been particularly enclosed and patriarchal in the former Military Frontier. The authorities had banned the sale of peasant land to “foreigners”, i.e. non-frontiersmen, and they also obliged the peasant population to organize into so-called zadrugas – extended family households that could remain sustainable with many male members absent for military service. Production for the market was limited, and trade primarily took place in local urban centers as well as across the Habsburg-Ottoman border.

A Serb “pandur” (infantryman), third from the left, 1881. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

A Serb “pandur” (infantryman), third from the left, 1881. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

After long being sheltered from economic liberalization, the former Frontier experienced an abrupt and traumatic transition into modernity. Once a preventive mechanism against impoverishment, zadrugas began to fragment into unsustainable land plots. Peasants were now subject to new tax burdens and intrusive laws while also losing certain customary rights that had alleviated their position under the old regime. Amidst a growing social crisis, the peasantry increasingly expressed its disdain for kaputaši (“coat-wearers”, i.e. officials and other town dwellers) and the Croatian state itself, which was governed by unionist politicians throughout most of the late Habsburg period. As proponents of Croatia’s integration with Hungary, the latter were popularly known as mađaroni (“Hungarophiles”) and were often accused of betraying the people’s interests by “selling” the state to the Hungarians. Peasant discontent in Dualist Croatia at times climaxed into popular uprisings and insurrections, some of which also involved the mass participation of the local Orthodox population.

A wooden Orthodox church in Sjeničak from 1715, date unknown. Source: sr.wikipedia.org.

A wooden Orthodox church in Sjeničak from 1715, date unknown. Source: sr.wikipedia.org.

Ever since the turn of the century, peasants were also being increasingly addressed by contemporary nationalist movements and their activists. Throughout the 19th century, the Serb nationalist movement in Croatia primarily functioned within the framework of autonomous Orthodox confessional institutions. Its primary goal had been to improve Orthodox religious infrastructure and maintain the autonomy of Orthodox confessional schools. While the latter competed with state interconfessional schools, it is worth emphasizing that the primary education system in rural Croatia-Slavonia remained severely underdeveloped throughout the late Habsburg period. In 1890, only 22,56% of Orthodox men and 10,76% of women were literate compared to 32,51% of men and 20,94% of women within the general population.

Aside from confessional autonomy, Serb nationalist demands were also directed towards questions of terminology and symbolic equality. Both the Croatian state as well as most currents of Croat nationalism insisted upon a civic definition of Croatdom, which rejected the idea that the local Orthodox could constitute a separate Serb nation. From their point of view, the former were merely Croats of “Greek-Oriental religion”, and this was also the official term used for the Orthodox confession throughout the late Habsburg period. Conversely, Serb nationalists demanded that the term “Serb” be employed for Croatia’s Orthodox, as well as legal equality and official usage of the Cyrillic script. While some of these demands were met when Orthodox notables allied with the government under Károly/Dragutin Khuen-Héderváry’s administration (1883-1903), Serb nationalism was increasingly understood as anti-state behavior and subject to persecution due to the state’s rising anxieties regarding South Slav irredentism.

Members of the Serb-nationalist gymnastic association in Dvor, 1904. Source: banija.rs.

Members of the Serb-nationalist gymnastic association in Dvor, 1904. Source: banija.rs.

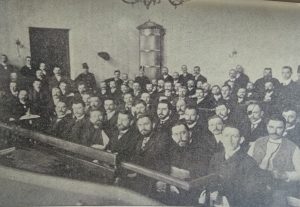

While they were largely excluded from the official political process due to Croatia-Slavonia’s elitist electoral laws, peasants and their troubles increasingly drew the attention of established political parties after the turn of the century. The Serb Independent Party and the Serb National Radical Party began emphasizing social issues in their political programs while also attempting to include the peasantry during their political assemblies. Politically engaged priests and teachers also contributed to the popularization of Serb nationalist ideas as figures of authority in local rural environments. All the while, as geopolitical tensions rose with the 1908 Bosnian-Herzegovinian Annexation Crisis and the 1912/3 Balkan Wars, the Croatian state intensified its persecution of Serb nationalism by locally suspending Serb cultural rights, dismantling confessional autonomy and imprisoning Serb political notables.

53 members of the Serb Independent Party on trial for high treason in Zagreb, 1909. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

53 members of the Serb Independent Party on trial for high treason in Zagreb, 1909. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

While some historians assume that a Serb identity had always been organically present among the local Orthodox, others have used constructivist arguments to argue that it arose as a product of conscious nationalist activism. As a general tendency, studies have usually examined the Croatian Serb community as an abstract whole or have focused on its political and economic elites, with relatively little attention being paid to the specific situation of the peasantry. While a bottom-up perspective is marginally present in the existing research, there remains ample room for more empirical studies that could examine this community’s changing relationship with nationalism during a period of strenuous social, cultural and political change.