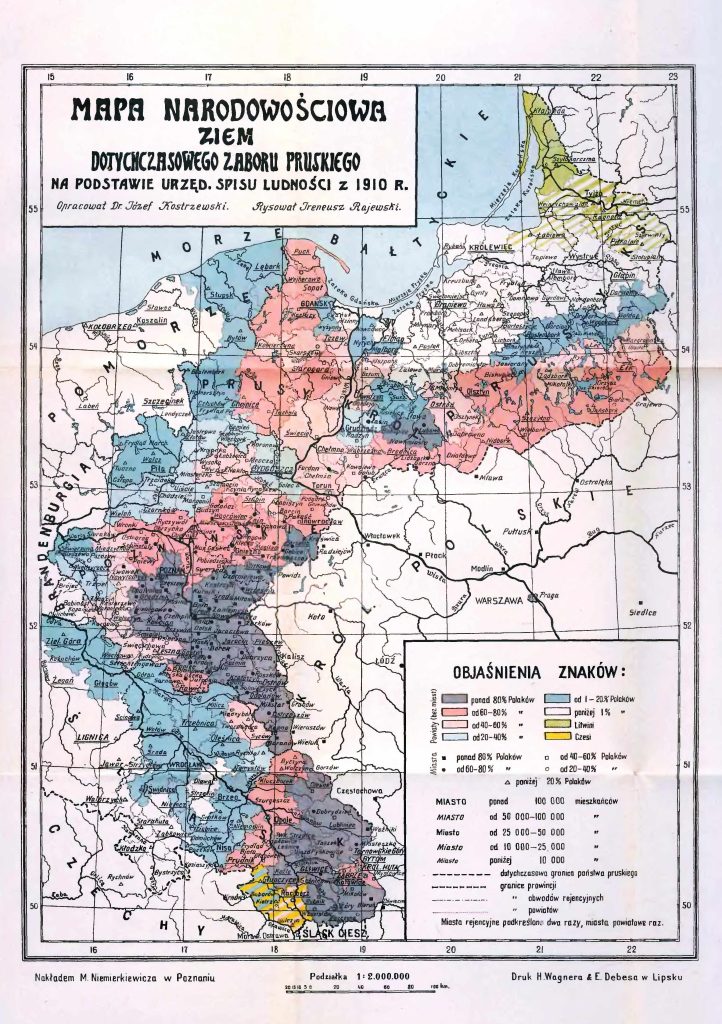

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Poles were the largest ethnic minority in the Kingdom of Prussia, which had been part of the newly founded German Empire since 1871. Poles mainly inhabited the eastern regions of Prussia, where they formed a clear majority in many districts. Both the Prussian administration and Polish activists treated the data on language as data on nationality. According to censuses, there were almost 3 million native Polish-speakers in total in 1890 and well over 3.5 million in 1910. The majority of them lived in the territories of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which Prussia had taken over in the course of the partitions of Poland at the end of the 18th century, although the borders were finally established as a result of the Congress of Vienna in 1815. This area, known as the Prussian Partition of Poland, comprised two Prussian provinces, Poznań and West Prussia, in addition to the small bishopric of Warmia in East Prussia. These territories had long traditions of Polish statehood, which were cultivated by the Polish nobility and intellectual elites. A fairly large Polish-speaking population also lived in Upper Silesia and the southern part of East Prussia, in the ethnographic region known as Masuria. At the time, these areas were among the least prosperous and least economically and infrastructurally developed in Germany, and the lack of development was also visible in the weaker access to primary education, especially in the villages. The level of industrialization also remained low (except for Upper Silesia). Most Polish-speakers were farmers, and their vast majority (over 95% in 1890) belonged to the Roman Catholic Church. (In the case of the Evangelical Masurians, attempts to build a Polish identity ultimately failed in the mid-20th century). They were thus distinguished by their religion from the mostly Evangelical (Lutheran) Prussian Germans.

The existing religious differences led to the emergence of an identification between Polishness and Catholicism. This was reinforced in particular by the “Kulturkampf” policy of Chancellor Otto von Bismarck in the years following German unification. In Polish-inhabited areas, restrictions against the Catholic Church proceeded simultaneously with the intensification of attempts at forced Germanization, which manifested itself, among other things, in the replacement of the Polish language and Polish teachers in elementary schools. Paradoxically, the Kulturkampf ended up thwarting any Germanization among Polish Catholics, while Germanization accelerated significantly among the small Polish Evangelical population. Catholic Polish peasants were in contact with Germans mainly as representatives of the ruling elites, officials of the Prussian state, and German settlers. The German evangelical settlers lived apart from their Polish surroundings, as they usually had their own (Evangelical) churches, schools and associations. Inter-confessional mixed marriages were frowned upon by both sides and almost never occurred. The alienation from German Evangelicals was deepened by the image, long disseminated by the Catholic Church and already established in the peasant imaginary, which equated them with heretics and enemies of the “true faith”.

In the German public sphere, there was a clear tendency to consider the large Polish population in the eastern territories as a threat to the integrity of the state. Not only the state authorities, but also the local German population often shared the image of the Poles as a dangerous internal enemy, and anything Polish was seen as an attack on Germanness. In the eastern Prussian provinces, anti-Polish German nationalist associations came into being, most notably the Deutscher Ostmarkenverein (German Eastern Marches Society, also known as “H-K-T” or “Hakata” after the surnames of its founders). Founded in Poznań/Posen in 1894, it quickly transformed into a nationwide organization.

In Germany, the image of the country’s eastern territories as colonial territories analogous to the American “Wild West” was widespread. Although the German Empire was in many respects a leader in Europe at that time in terms of civil rights, the rule of law, and modern social legislation, the discriminatory measures against the Polish population were far removed from these standards. Both among Polish national activists of the time and in later Polish historiography, one can often come across the conviction that the measures taken by the state against the Polish population had a significant impact on the formation of national identity among the peasants.

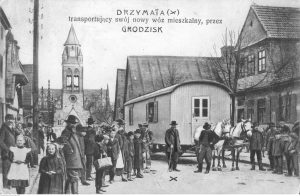

The fundamental and existential way in which state policies could affect peasants can be illustrated by the famous example of Michał Drzymała, a peasant from the Province of Poznań. Due to a law which in practice allowed the authorities to limit the Polish population’s right to build new houses, he was forced to live in a wagon. His was the most famous, but not the only case of its kind. Since Prussian state measures were aimed at stunting Polish material and economic development, the Polish civil society and associational sphere responded by helping Polish peasants obtain loans, buy land or develop and modernize their farms. Both the Prussian authorities of the time and, to a certain extent, later Polish historiography emphasized the importance of such associations in promoting national ideas among broad swaths of the population. However, it seems that for the peasants who took part in such initiatives, the economic aspect of these undertakings may have been of greater importance. At any rate, peasants could meet and cooperate with the Polish nobility and intelligentsia in such associations, most of whom had a crystallized Polish national identity.

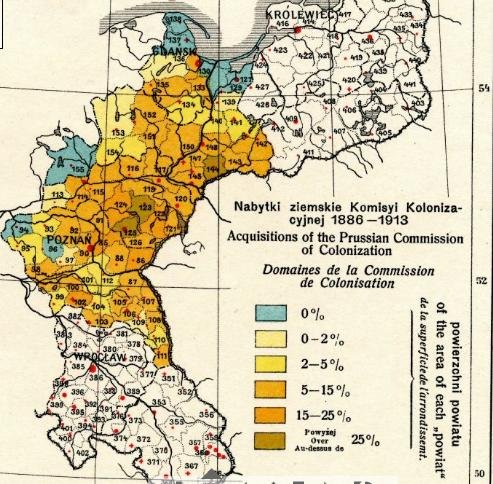

Mutual understanding and cooperation between the peasantry and the nobility was hardly possible without prior enfranchisement and the abolition of serfdom. Most of these reforms had been carried out by the Prussian authorities in the years 1823–1850. They changed property relations and spurred a transition to capitalist economy in the countryside. As compensation for the abolition of serfdom, the nobility increased their landholdings, while the peasants were divided into a class of farmers, who worked their own farms, and landless day laborers or farmhands. Anti-Polish German economic activity could unite these groups. In particular, the Colonization Commission (Königlich Preußische Ansiedlungskommission für Westpreußen und Posen), established in 1886 and subsidized by the government, had the task of buying land from Polish owners and then creating more favorable conditions for its acquisition by German farmers. In some parts of the Province of Poznań, the Colonization Commission collected a considerable amount of agricultural land. This activity made the land less accessible to Polish peasants, also because government intervention raised land prices considerably.

Despite the obstacles, Polish peasants in the Prussian partition benefited from the general development and modernization of agriculture which took place in these areas at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. In this respect, the Prussian partition became the most economically developed and prosperous of all three Polish partitions. Progress was not only visible in the economic sphere. These lands also stood out in terms of the educational level of literacy of society compared to most areas of Central and Eastern Europe. Towards the end of the partition period, the total share of illiterates in the Prussian partition was only around 5%. Although access to education in the rural areas was much worse than in the cities and the school network in the Polish areas was generally much sparser compared to other parts of Prussia, the situation gradually improved here too. As a result, the number of peasants reading Polish newspapers slowly increased. At the same time, education was another field of Polish-German rivalry. The state authorities tried to eliminate Polish language from schools and replace it with German. Already in the early 1870s, no subject except religion was allowed to be taught in Polish, and at the end of the 1880s it was forbidden to organize Polish language classes in any form. Measures aimed at removing the Polish language from religious education at the beginning of the 20th century provoked a harsh reaction among the Polish population. The events that went down in history as school strikes affected large parts of the provinces of Poznań and West Prussia. The broad participation of peasant children and peasants themselves in the resistance against the authorities is sometimes presented as evidence of their advanced Polish national consciousness. However, it is worth remembering the role that religious issues played in this matter, including the probably widespread belief in the invalidity of prayers recited in a foreign language.

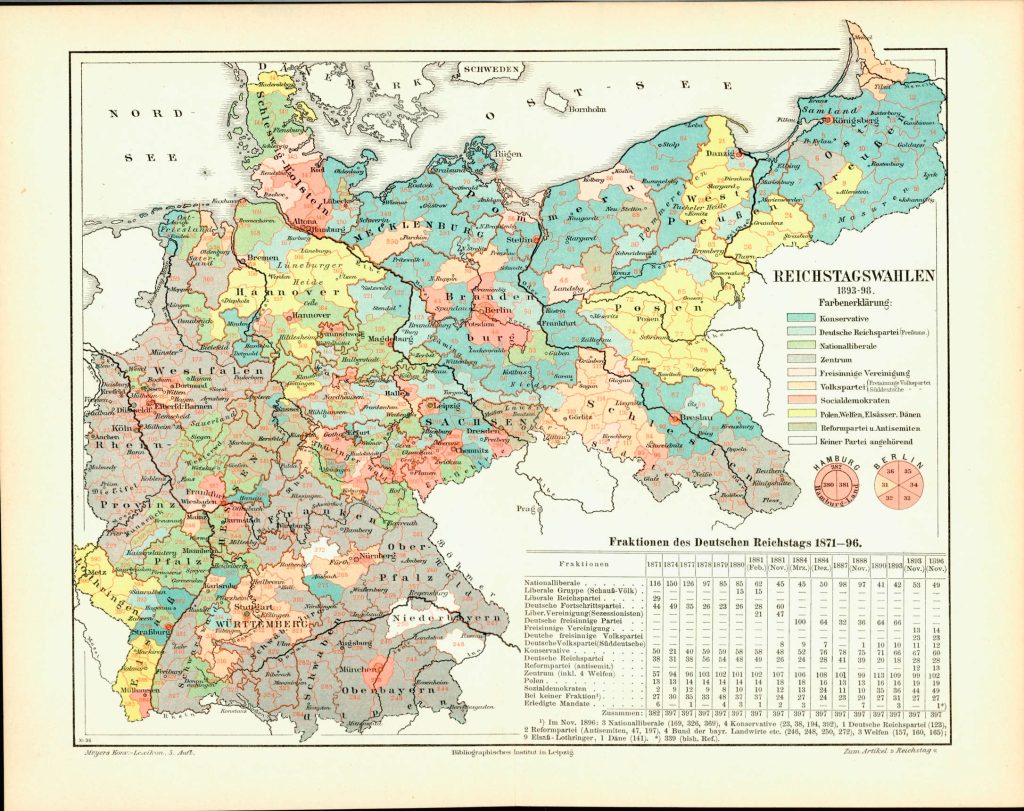

The lack of formal schooling in Polish was compensated by societies that promoted reading in Polish and Polish patriotism, primarily the Towarzystwo Oświaty Ludowej (People’s Education Society) and later the Towarzystwo Czytelni Ludowych (People’s Libraries Society). Such educational and cultural societies provided another channel through which Polish peasants could familiarize themselves with Polish national ideology. In addition to the former nobility and intelligentsia, Catholic priests were also often involved in the work of associations and national agitation and relied on the infrastructure the parish network provided. They probably had a crucial impact on the development of new political attitudes among the peasantry. Religious and national issues came together especially in the election campaigns for the Prussian Landtag and the all-German Reichstag. Polish peasants, having the right to vote, were the target of lively agitation. Their reactions may suggest that they resonated with the national platform to some extent, often electing representatives of the “Polish faction”, usually cooperating with the Zentrum Party, which represented the political interests of Catholics in the German Empire.

Numerous works have been written on national issues in the Prussian partition, sometimes touching on the question of peasant participation. It should be noted that some non-Polish authors have suggested, especially recently – such as Jens Boysen in his book published in 2008 – that ordinary Poles in Prussia were not particularly keen on national issues until World War I. To date, however, the assumption that the feeling of belonging to Poland had always been “dormant” among the peasants and only needed to be “awakened” has remained noticeable in many Polish works. It is therefore often assumed that the peasants consistently resisted the policies of the occupying power from the very beginning, and all examples of resistance are supposed to confirm this. A little less attention has been paid to the question of whether and to what extent such examples reflected the mainstream and to what extent they may have been merely isolated exceptions. There is often a lack of deeper reflection on how many peasants were actually involved in a particular event or organization in comparison with other social categories, whether they played a significant or only a marginal role, what milieu these peasants came from and what might have prompted them to become involved in such matters. Historiography from the period of the Polish People’s Republic naturally led the way in emphasizing the participation of peasants and other representatives of the lower social strata in the struggle against the “occupiers”. But in general, these publications often focused too much on the Polish national press and too little on the documents the Prussian administration produced. Although the researchers noted the importance of the state agency in the process of mobilizing Polish peasants under national slogans, it seems that the question of why certain actions of the state provoked a reaction from the peasants and why they considered these particular issues important still requires more detailed research.

Our Focus Areas

One basic problem with attempts to probe into peasants’ political participation in the Prussian partition seems to be the temptation to make overly superficial generalizations that do not take into account the internal diversity of this area, as well as an excessive focus on the Province of Poznań itself. When considering the spread of national ideas among Polish peasants across the entire territory, it would be useful to pay more attention to the regional specificities of individual areas. The territories of the Prussian partition were definitely not a homogeneous area in terms of the social conditions that influenced the formation of national identity. The Province of Poznań was characterized by the strong presence of Polish nobility and intelligentsia. Polish-speakers prevailed in the total population of the province. The area around Gniezno/Gnesen, located near the border with Congress Poland, had a very Polish, yet decidedly rural character. This small city was the archbishopric seat of the Primate of Poland and is traditionally considered the first Polish capital. At the same time, the Gniezno district, next to the Żnin/Znin district, was one of the most affected by the activities of the Settlement Commission. As much as 39% of the district’s area was in the possession of the Commission in 1913. As a result, the number of Germans outside the cities in the district increased and a ring of German villages surrounded Gniezno. However, the ethnic makeup was different in other parts of the Province of Poznań. In Leszno/Lissa and Wschowa/Fraustadt districts in the southwest of the province, the German population significantly outnumbered the Polish population. The cities were almost entirely German. Some of the landed estates also belonged to German aristocratic families.

In the province of West Prussia, the share of people speaking German in the total population was much higher than in the Province of Poznań. In many areas there was a lack of Polish landed gentry, and the aristocratic social class was German. Similarly, in many cities, the German population predominated. A particularly interesting case is the area of Kashubia located here. The Kashubian population differed from the rest of the Polish population, particularly in linguistic terms. The Prussian authorities emphasized the existence of a Kashubian language separate from Polish and spoken mainly by the lower classes. However, initiatives to build a Kashubian identity separate from Polish did not achieve much success. Polish national ideas reached Kashubia with some delay, and the main center of Polish national and cultural life was Kościerzyna/Berent.

Warmia, a region located in the province of East Prussia, was also part of the Prussian partition. Before the first partition in 1772, it was an autonomous episcopal principality, inhabited by German- and Polish-speaking Catholics, in contrast to the surrounding areas, where Evangelicals (German- and Polish-speaking) dominated. Polish-speakers were concentrated in its southern part, in the districts of Olsztyn/Allenstein and Reszel/Rößel. The towns were mainly German. This situation encouraged the formation of a local identity based on religion and loyalty to the episcopal authority. After the annexation to the Kingdom of Prussia, most of the Polish nobility left Warmia. Local Polish peasants found the German language attractive and the influence of German culture among them grew throughout the 19th century. While in most other areas of the Prussian partition, including Kashubia, the activities aimed at popularizing Polish identity among peasants brought clear results, it seems that the response was much more lukewarm in Warmia. The initiative was taken mainly by Polish nationalist activists from other parts of the Prussian partition.

A more thorough study and comparison of different cases from the Prussian partition, taking into account the local specificity of each area, should allow for a better understanding of the processes of national identity formation among local peasants. Despite the significant and rich achievements of previous Polish historiography on national issues in the Prussian partition, it helps us understand the motivations and perceptions of peasants only to a very small extent. Therefore, it seems reasonable to take a closer look at the Polish peasant population, treated by the Prussian state as part of an unwanted national minority.